Why the West Was Wrestling's True Frontier

Before wrestling went national, its soul was rooted in place. A deep dive into the GWA's legendary territory map and how the American West became the promotion's most unforgettable character.

A speculative look into how geography and culture shaped wrestling territories of the past.

The Drive Between El Paso and Denver

Picture this: It's 3 AM on a Tuesday in 1973, and you're riding shotgun in a beat-up Mercury with "Outlaw" Jesse Hawkins behind the wheel. The radio signal from XEOJ-AM is the only station coming in now, the other signals dropped somewhere between Roswell and nowhere. Outside the passenger window, the high desert of New Mexico stretches endlessly under a canopy of stars that city folk never see. You've got 400 miles of this ahead of you before you hit Denver, where Hawkins is scheduled to defend his GWA World Heavyweight Championship tomorrow tonight.

This isn't unusual. This is Tuesday.

Wrestling was different. While modern wrestling travels between identical corporate arenas via chartered jets and ad-sponsored tour buses, territorial wrestlers measured their careers in highway miles and gas station coffee. The journey from El Paso's Liberty Hall to Denver's Rainbow Music Hall wasn't just transportation, it was transformation. Every mile between venues wasn't empty space to be conquered, but living territory that shaped the wrestlers, the stories, and the very soul of professional wrestling in the American West.

As GWA Founder "Redwoods" Jack Carson once observed, "The West is motion. It's the perpetual now, always becoming, never arriving." This wasn't philosophical musing—it was business reality. The vast distances that made the West wrestling's natural laboratory also made it the most demanding testing ground in professional sports.

The Geography of Identity

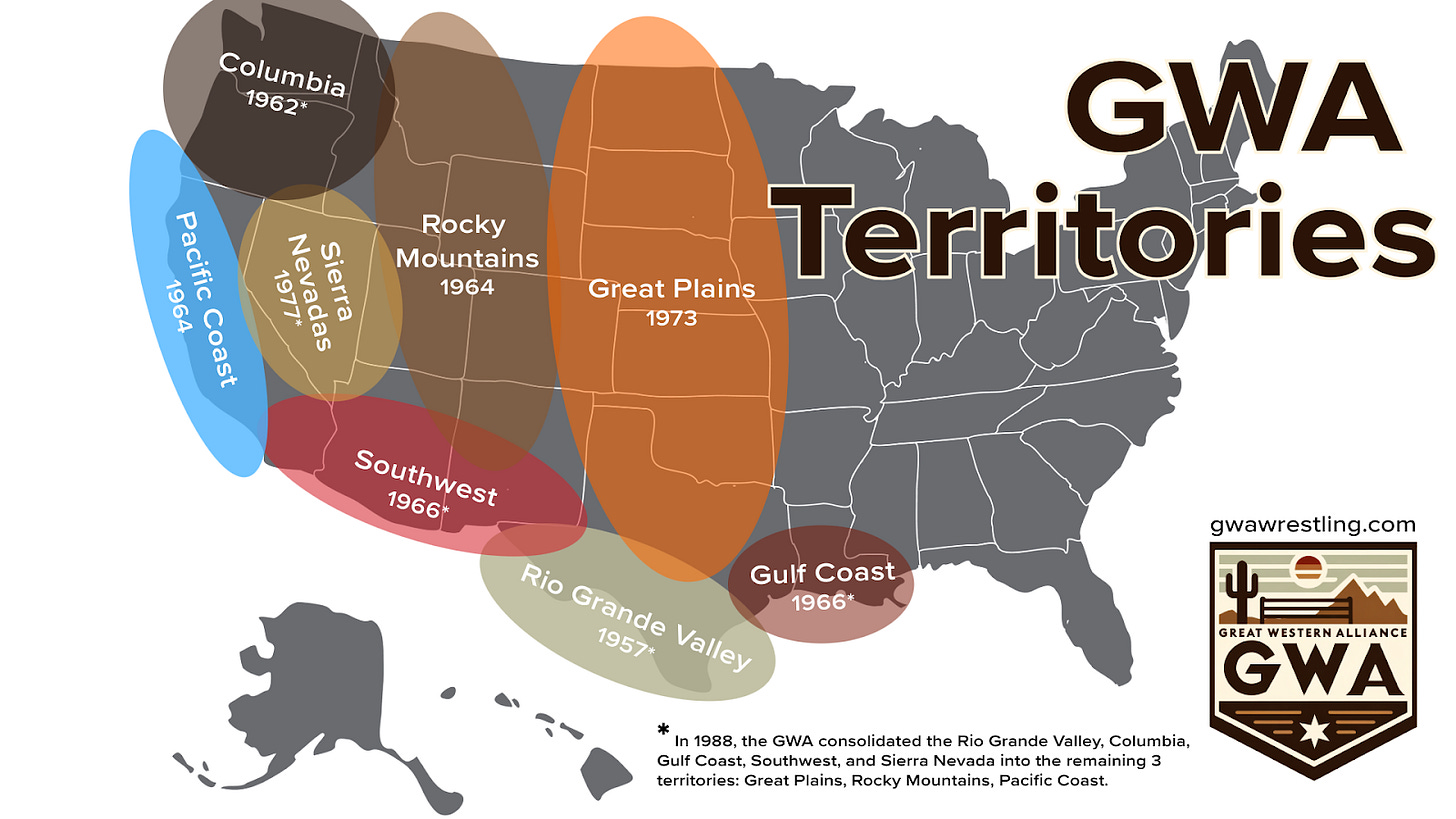

The territorial system emerged from practical necessity, but in the West, it became something approaching art. Where other regions might support a single major promotion, the sheer scale of the American West demanded multiple territories, each developing its own distinct character shaped by geography, industry, and culture.

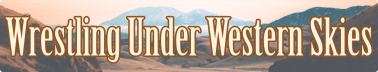

The Great Western Wrestling Alliance understood this from its founding. When Miguel "Rio Grande" Ramirez and Jack Carson first mapped their territorial ambitions in 1958, they weren't thinking like corporate executives drawing arbitrary market boundaries. They were thinking like the freight-hopping wanderer and the border-crossing artist they were—following the natural contours of culture and community that the landscape itself had carved.

Territory boundaries followed the rhythms of regional life: logging seasons in the Pacific Northwest, oil booms along the Gulf Coast, mining schedules in the Rocky Mountains. Each territory developed not just its own roster of wrestlers, but its own wrestling philosophy, shaped by the people who lived there and the landscape that defined their daily reality.

The genius of the GWA system was recognizing that these differences weren't obstacles to overcome, but strengths to celebrate. As Carson put it, "You can't package the horizon. The minute you try to fence it in, label it, sell it... that's the minute it slips through your fingers like desert sand."

Each Territory Its Own Wrestling Culture

The Border Foundation (1958)

The Rio Grande Territory emerged because other promotions considered the border region "too dangerous" to run shows. Ramirez saw opportunity where others saw only prejudice, establishing a territory that celebrated cross-border culture rather than exploiting it. Centered in San Antonio with strong connections to Monterrey, this became the foundation for everything that followed.

Here, bilingual storytelling wasn't a gimmick—it was necessity. Crowds that spoke Spanish and English (often simultaneously) demanded wrestlers who could connect in both languages and both cultures. The lucha libre tradition mixed with Texas brawling created something entirely new: a wrestling style that was authentically bicultural.

Pacific Dreams and Logging Camp Realities (1960-1964)

The Columbia Territory grew from the wild reception during the GWA’s 1962 Great Rail Rumble and Carson's personal history and partnerships with logging companies seeking winter entertainment for their workers. When the trees couldn't be cut, the men needed somewhere to direct their energy. Wrestling provided both outlet and identity.

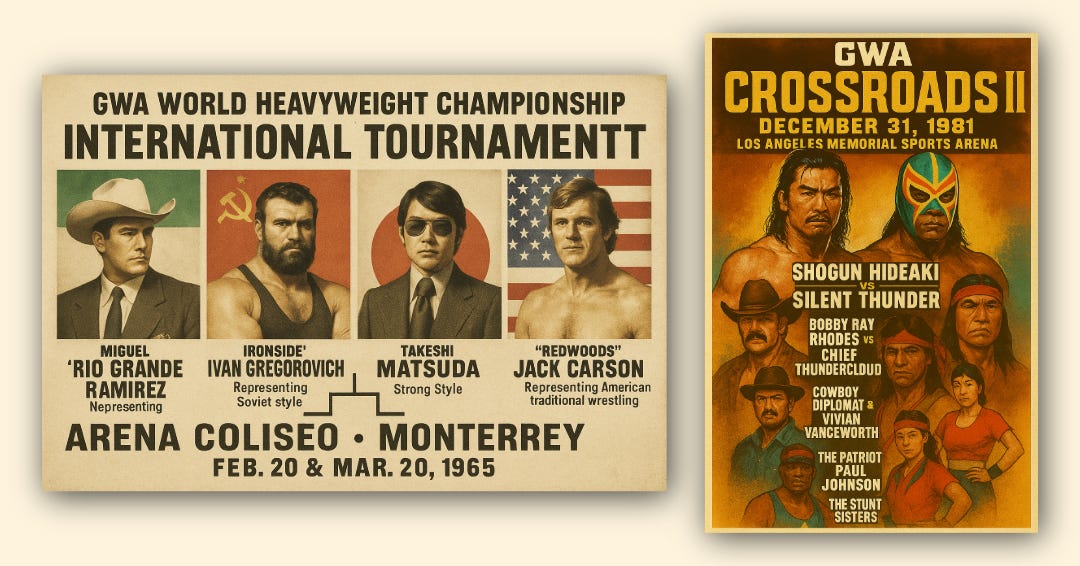

Meanwhile, the Pacific Coast Territory emerged when Hollywood stunt performers approached the GWA about wrestling between film jobs. The fusion of traditional wrestling with theatrical elements didn't diminish authenticity—it enhanced it, creating production values that elevated the entire industry.

These parallel developments showed the West's capacity for innovation without losing its core identity. Whether in a converted logging camp or the Grand Olympic Auditorium, wrestling remained rooted in genuine competition and authentic storytelling.

Mountains, Deserts, and Accidental Discoveries (1964-1967)

The Rocky Mountain Territory formed around a real feud—"Mountain Man" Mark Jensen's legitimate conflict with a corrupt mining executive. The high-altitude venues didn't just provide atmosphere; they created a proving ground that produced particularly resilient wrestlers. As Jensen himself noted, "You fight different at 8,000 feet. Everything is harder."

The Southwest Territory existed only because of a booking error. When "El Águila" Pedro Ramirez was accidentally sent to Phoenix instead of Portland, his impromptu performance revealed an untapped Hispanic market that rival promotions had completely ignored. Sometimes the best territorial expansions happened by accident.

The Gulf Coast Territory formed when "Bayou" Benny Lacroix led a walkout from a rival promotion, bringing much of entire roster to the GWA. The Frontier Circuit developed organically when the Frontier Brothers began performing in small towns to offset travel expenses between major venues.

These individual stories of origin—born of opportunity, necessity, and sheer accident—were all woven into a larger tapestry where the Western landscape itself became the most influential character on the roster.

This organic, place-based evolution—born from principle, necessity, and sheer accident—created a rich tapestry of wrestling styles across the West. Each territory developed a unique flavor that changed with the times, reflecting the cultural and geographical forces that shaped it.

The Landscape as Character

In territorial wrestling, geography wasn't just setting—it was cast member. The high desert of Arizona produced different stories than the oil fields of Texas. Logging camps in Oregon demanded different heroes than casino towns in Nevada.

Venues reflected their communities: high school gymnasiums with fold-out bleachers in farming towns, converted warehouses in industrial cities, fairground rings that went up and came down with the carnival. Each space carried its own energy, its own expectations, its own relationship between performer and audience.

Carson understood this instinctively: "The real West is alive in the miles between—those long stretches of highway where the radio fades to static and your mind starts dancing with defeated ghosts." The journey between venues wasn't dead time; it was where wrestlers developed the road wisdom that informed their ring psychology.

Weather, altitude, and terrain became storytelling elements. A feud that began in the humid heat of Houston carried different weight when it continued in the thin air of Denver. The same wrestler might work as a sympathetic underdog in a small farming community and as an arrogant outsider in a major metropolitan market.

Greater than the Sum of Its Parts

What made the GWA territories revolutionary was their embrace of cultural complexity. Rather than imposing a single wrestling style across all regions, they allowed each territory to develop its authentic voice while maintaining overall continuity.

Mexican lucha libre influence wasn't confined to border territories—it enriched wrestling throughout the Southwest. Native American wrestling traditions in mountain regions provided storyline depth that went beyond stereotype to genuine cultural respect. Industrial worker culture in mining and logging areas created heroes who looked and sounded like their audiences.

Military influence near bases like Fort Huachuca provided both talent and audiences familiar with discipline and physicality. Oil boom prosperity in Texas supported larger venues and higher production values. Each factor shaped not just local wrestling style, but the stories that territory could tell convincingly.

As Carson observed, "I found it freight-hopping through Montana in '49... Found it again in Miguel's aunt's kitchen in San Antonio, where the smell of chorizo mixed with turpentine from her paintings." The GWA succeeded because it recognized these authentic cultural intersections rather than trying to homogenize them.

Why It Mattered Then, Why It Matters Now

The territorial system represented something precious that modern wrestling has largely lost: the understanding that place matters, that community identity isn't just marketing but substance, that authentic regional differences enrich rather than weaken the overall product.

When wrestlers traveled between GWA territories, they weren't just changing venues—they were crossing cultural boundaries that demanded adaptation, growth, and genuine respect for local traditions. A wrestler who could succeed in the bilingual intensity of San Antonio, the logging camp toughness of Portland, and the desert survival mentality of Phoenix had proven something about themselves that no corporate training facility could teach.

The loss of territorial wrestling meant more than the consolidation of business—it meant the flattening of American wrestling's cultural diversity. Today's discussion about local versus global culture, about authentic community versus corporate homogenization, about respecting regional differences versus imposed uniformity, all echo the choices that wrestling made when it abandoned the territorial system.

The GWA proved that celebrating differences didn't weaken the product—it strengthened it. Their territorial map wasn't just business strategy; it was cultural preservation.

Setting the Stage for Epic Journeys

Understanding this territorial landscape is essential for appreciating the true weight of stories like the Renegade Riders saga. When a wrestler crossed from the Rio Grande Territory into the Great Plains Territory, they weren't just changing addresses—they were entering a different world with different rules, different audiences, and different measures of success.

The betrayal that shattered the Renegade Riders wasn't just personal—it was wrapped in geographical, cultural, and professional consequences. The journey that followed crossed not just state lines but cultural boundaries, each territory offering its own form of sanctuary or challenge, its own test of character and resilience.

Carson's vision of the West as "perpetual motion" captured something essential about territorial wrestling: it was always becoming, never arriving, always reaching for something just beyond its grasp. That restless energy, that constant journey between who you were and who you might become, that was the true magic of wrestling's territorial age.

As we follow these stories across the map, remember that every highway mile mattered, every venue had its own personality, and every territory demanded that wrestlers prove themselves not just as athletes, but as storytellers worthy of their landscape's vast and unforgiving stage.

The territory map wasn't just geography—it was a leading character.