The Smile We Mistook For Strength

Part 1 of The Second Opponent: On Wrestling, Restraint, and American Strength

In 1908, a twenty-nine-year-old farm boy from Humboldt, Iowa became the most celebrated athlete in America. His name was Frank Gotch, and when he defeated the seemingly invincible European champion Georg Hackenschmidt to win the World Heavyweight Wrestling Championship, the nation erupted. Police had to control the joyous crowds that mobbed him in the streets of Chicago. President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to the White House—twice. Three years later, thirty thousand people would pack Chicago’s Comiskey Park to watch him defend his title.

The newspapers praised Gotch’s “moral courage and strength of character.” They called him “the one bright spot on the darkened horizon of the wrestling game,” a man who abstained from liquor and tobacco, who returned to Iowa between matches to work as a banker and stock farmer, who embodied everything decent about American manhood. The New York Times marveled that never in his long career had there been “a hint of scandal or foul play associated with him.”

But these same newspapers also documented—often in the very same articles—that Gotch greased his body with oil before matches so opponents could not grip him. That he gouged eyes and raked faces with his knuckles. That he employed what one referee delicately called “needless acts of absolute cruelty” against already beaten opponents. That when facing the Polish wrestler Stanislaus Zbyszko, Gotch ambushed him during their pre-match handshake, pinning him in just over six seconds in what many considered an unsporting trick.

Wrestling legend Lou Thesz, who spoke with old-timers who had known Gotch personally, stated it plainly decades later: “Gotch was, for lack of a kinder description, a dirty wrestler.”

The remarkable thing is not that both versions of Frank Gotch existed. The remarkable thing is that they coexisted without apparent contradiction in the American imagination.

When Georg Hackenschmidt complained after their 1908 match that Gotch had oiled his body and employed illegal tactics, American journalists did not deny these facts. They reframed them. One Wisconsin sportswriter noted that oiling one’s body before a match was “not a new trick” and suggested that Gotch’s mentor might have taught him this ploy. The referee, Ed Smith, acknowledged Gotch’s rough tactics but described them as behavior that was “customary in any match of importance.”

The message was clear: what Europeans might call foul play, Americans called competitive fire. What Hackenschmidt experienced as a violation of sporting ethics, American observers interpreted as evidence of Gotch’s superior will to win.

This was not hypocrisy being exposed. This was hypocrisy being celebrated.

Gotch’s personal virtue—the fact that he did not drink, that he was a respected businessman—was used to sanctify his competitive brutality rather than to question it. We had learned to separate personal morality from competitive ethics so completely that a man could gouge eyes and oil his body and still be praised for his moral courage. We had made dominance inseparable from strength, and strength inseparable from virtue, until the categories merged into a single imperative: win, and you are proven good.

By the time Gotch faced Hackenschmidt again in their highly anticipated 1911 rematch, rumors of a fix were so persistent that Chicago’s Chief of Police canceled all betting on the match. The stadium owner, Charles Comiskey, convened an emergency meeting with wrestlers and promoters and declared he “wouldn’t allow them to stage this robbery of the public” in his facility.

Thirty thousand fans came anyway.

The 1911 rematch provides the clearest window into what Gotch’s approach to competition actually meant. Hackenschmidt arrived in Chicago with a badly injured knee. The rumors about how he sustained that injury vary—some claim Gotch’s camp paid a training partner to deliberately wreck the Russian Lion’s leg, others say it was a legitimate accident—but what is undeniable is what happened once the match began.

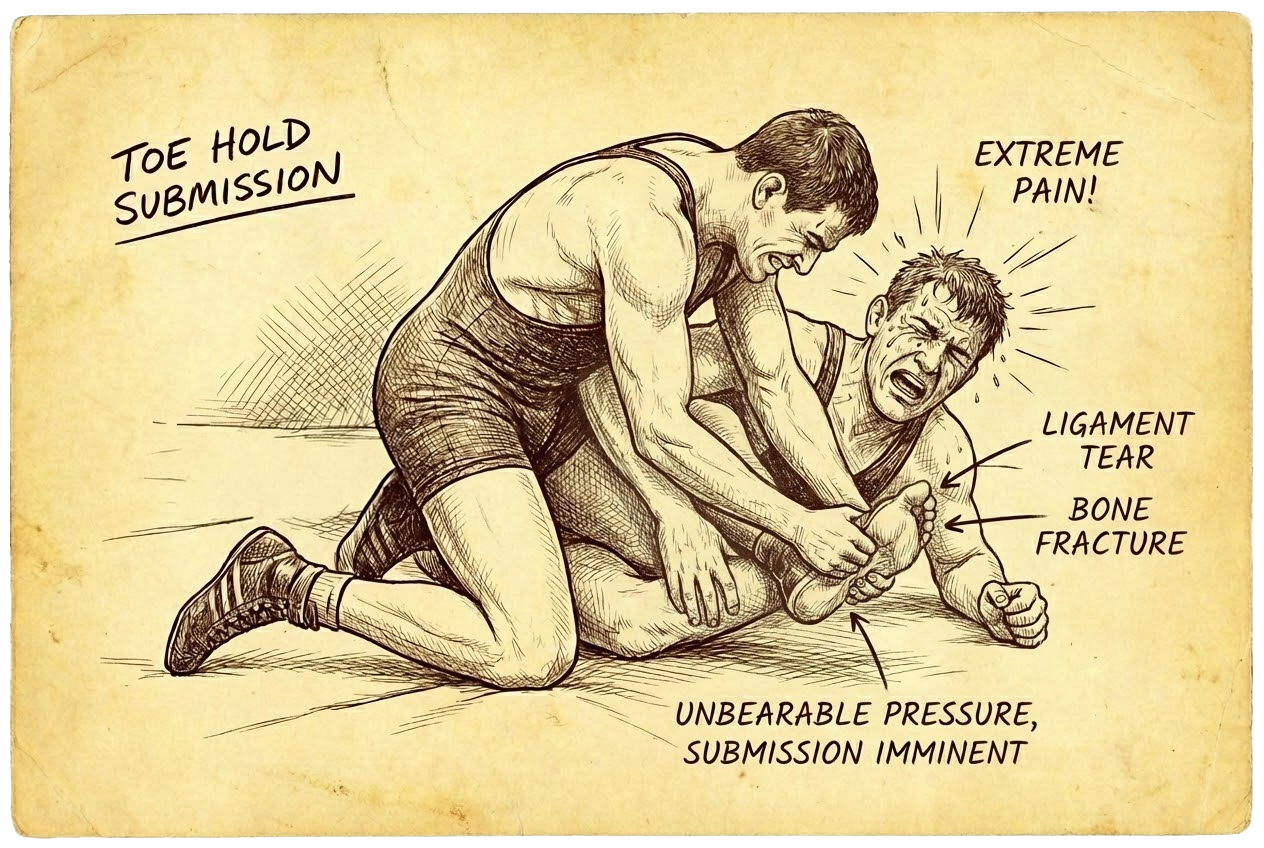

Gotch, facing a clearly compromised opponent, immediately targeted the injured knee. He won two straight falls in less than thirty-five minutes, finishing Hackenschmidt with his feared toe-hold submission that tormented the damaged leg. The crowd had come expecting an epic contest. They witnessed something closer to an execution.

The crowd left feeling, as one Chicago sportswriter put it, that “something had been done to them—they knew not exactly what, but something.” They knew. They came back for more.

In the aftermath, one thing became clear: Gotch’s victories required not merely superior skill but the willingness to exploit any advantage, to brutalize when brutality would ensure success, to abandon constraints that others maintained. His smile over beaten opponents was not the smile of someone confident in his superiority. It was the smile of someone who needed to dominate because he could not imagine worth that did not come from domination.

And then we built an entire culture on that principle.

It comes down to Frank Gotch’s smile. Not the physical expression itself—few photographs capture it clearly—but what it represented standing over beaten opponents. It was the smile that became a template for what champions should be. The smile America saw and called strength.

What if we were celebrating the wrong thing?

What if competition tests not merely who can defeat whom, but whether we can restrain ourselves when domination becomes available? What if there is a second opponent present in every contest, one that remains invisible until we look for it—not the person across from us, but the impulse within us to dominate when loss threatens our identity?

Competition has two opponents: the one we face, and the one we become. America has spent a century celebrating those who defeat the first while excusing those who fail the second.

Frank Gotch defeated Hackenschmidt, Jenkins, Zbyszko. He won match after match, championship after championship. He trained obsessively for those external opponents. He studied their weaknesses. He refined his technique. He won.

But he never recognized there was a second test happening simultaneously—whether he could restrain his impulse toward brutality when brutality would bring advantage. Whether he could maintain standards when abandoning them would make winning easier. Whether he could govern himself rather than simply defeat others.

He lost that test completely. And America made him a hero anyway, because we had learned to measure strength by the wrong standard.

What did Gotch’s career actually teach? Not the eulogy version. The pattern version. That effectiveness justifies method. That winning proves virtue. That restraint is what you practice when you lack the power to dominate.

Contemporary observers—those willing to look past the mythology—saw something else. Ed Smith, the same referee who had presided over both Gotch-Hackenschmidt matches and publicly defended Gotch’s tactics as “customary,” later admitted in more candid moments that he had witnessed “needless acts of absolute cruelty” in the ring. Smith suggested that a truly courageous sportsman “is willing to let up on a beaten foe and not punish needlessly,” implicitly acknowledging that Gotch did the opposite.

Former world champion Charlie Cutler told Lou Thesz that Gotch would “check the oil”—an extremely unsportsmanlike maneuver—and that he made sure to have referees who would overlook his violations. These were not later revisionist takes from jealous rivals. These were accounts from people who were there, who watched Gotch work, who understood that his dominance required more than skill.

Wrestling in Gotch’s era was already developing a reputation for fixed matches and shady dealing. His success was supposed to redeem the sport, to prove that genuine competition could still exist. Instead, the tactics he employed and the adulation he received for employing them helped establish the template for what would come after: a world where trust became impossible, where everyone assumed everyone else would cheat given the opportunity, where restraint looked like naive vulnerability.

By the 1920s, professional wrestling’s reputation had collapsed. The public had grown cynical. The double-crosses and fixed matches that had seemed clever in the moment had destroyed the foundation of trust necessary for sustained public investment in outcomes. People stopped believing any of it mattered.

The sport ate itself. And Frank Gotch, celebrated as its greatest champion, had shown it exactly how.

There is a moment I return to when I think about Gotch. Not from any specific match, but from the accumulated weight of the historical record. It is the moment when Hackenschmidt, the cultured European champion who prided himself on honorable competition, realized what was happening in their 1908 match. When he understood that his American opponent had no intention of competing within the constraints Hackenschmidt considered fundamental to sport itself.

Hackenschmidt complained to the referee. The referee dismissed the complaint. The match continued. Gotch won.

In that moment, a choice was presented to everyone watching, everyone reporting, everyone making sense of what they had witnessed. They could recognize that Gotch had won by abandoning constraints his opponent maintained. They could see that effectiveness and virtue are not the same thing. They could understand that defeating someone does not automatically justify the methods used to defeat them.

American culture made a different choice. We decided that Gotch’s victory proved his approach was correct. We decided that Hackenschmidt’s complaints were the whining of a sore loser. We decided that winning was the test that mattered, and that how you won was irrelevant as long as you won.

We made that choice over and over, in wrestling ring after wrestling ring, in newspaper article after newspaper article, until it became so automatic we forgot we were choosing. Until it became simply how things were. Until Frank Gotch’s smile became the face of American strength.

But there was always another test happening. A harder test. The test of whether we could restrain ourselves when domination was available. Whether we could maintain continuity of character across victory and defeat. Whether we possessed enough strength to govern our own impulses rather than simply defeat external opponents.

Gotch never recognized that test existed. His smile proved it—the smile of someone who believed dominance proved virtue, who could not imagine that the ability to brutalize others might be evidence of weakness rather than strength, who never understood that there was a second opponent waiting in every contest.

The second opponent he never defeated. The one that mattered more.

We will spend the rest of this series examining what that second opponent is. But first, we must understand what we are up against. The voice that arrives like a reflex whenever restraint is suggested: That’s just how the world works. Power dominates. Restraint is naïve.

That voice needs an answer. Because until we answer it, we will keep mistaking the smile of the predator for the strength of the protector.

Next week: The moral alibi—hustle, power realism, and the language we use to make dominance invisible.

This is Part 1 of a five-part series, titled The Second Opponent: On Wrestling, Restraint, and American Strength examining competition, restraint, and what strength actually requires. The full series:

Jesus and the Reversal of Power

Those Who Passed the Hidden Test

What Happens When Restraint Dies